Book Women, let’s do it again

July 6, 2010

Following the Great Depression and the Flood of 1930, Kentucky was considered one of the poorest states in America. Residents of Eastern Kentucky, many of whom could trace back their heritage to pre-Revolutionary War days, were living lives similar to their ancestors, with no indoor plumbing, electricity, telephone service or radio access.

In 1933, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration sent representative Lorena Hickock, to report on the conditions in the area. What she reported stunned not only government officials, but also President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In forming the relief program, the New Deal, Roosevelt allowed opportunities for male Kentuckians to work on building projects such as erecting schools, health clinics, roads, park facilities, and community centers. Unfortunately these projects required heavy manual labor, excluding the female population. Thus, jobs promoting social and cultural awareness were created to put female heads of households to work in medical facilities, schools, and libraries.

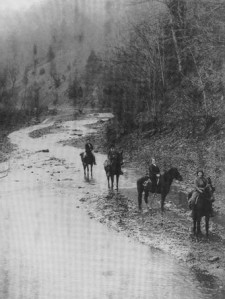

One of these programs was eastern Kentucky’s Pack Horse Library Project. Established in 1935, the Pack Horse Library Project was aimed at providing reading materials to rural portions of Eastern Kentucky with no access to public library facilities. Librarians riding horses or mules traveled 50 to 80 miles a week up rocky creek beds, along muddy footpaths, and among cliffs to deliver reading materials to the most remote residences and schools in the mountains. Some homes were so remote that the book women often had to go part of the way on foot, or even by row boat.

Materials used by the pack horse libraries were stored in headquarters libraries, usually located at the county seat. Collections consisted mostly of damaged books and magazines that larger libraries no longer wished to circulate, as well as out-of-date textbooks once used by schools or churches. (The W.P.A. only funded librarian salaries; it did not provide funds for collection development.) When demand for materials exceeded the supply, scrapbooks of magazine clippings, anecdotes, local recipes, and newspaper clippings were made by the librarians as additional resources for the collection. These became very popular in the region, enough so that patrons began making scrapbooks of their own recipes, family history, sewing patterns and child-rearing advice for circulation by the pack horse librarians throughout the community.

By 1936, handmade and donated materials could not sustain the circulation needs of the pack horse patrons. Surveys of readers found that pack horse patrons could not get enough of books about travel, adventure and religion, and detective and romance magazines. Children’s picture books were also immensely popular, not only with young residents but also their illiterate parents. Per headquarters, approximately 800 books had to be shared among five to ten thousand patrons. To help overcome the shortage, Lena Nofcier, Chairman of Library Service for the Kentucky PTA, began the Penny Fund Plan which called on every PTA member in the state to contribute one penny toward the purchase of new books. Nofcier also petitioned the help of boy scout troops, Sunday-school classes, private organizations/clubs and children’s school groups to locate or donate books for the pack horse libraries. Through her efforts, existing pack horse collections not only grew, but eight new pack horse libraries were also established.

Despite the ongoing shortage of materials, the Pack Horse Library Project was considered very successful, and one of the most unusual library services ever offered in the country. During its height, the program boasted 30 libraries serving close to 100,000 Eastern Kentucky residents. Interest in ideas outside the realm of Appalachia, an appreciation for education, and an introduction to global cultures were fostered by the program in an area where one-room schoolhouses and churches were the only means of learning about the world.

Despite their success, the pack horse libraries came to an end in 1943 when the W.P.A. withdrew its funding from the project. Consequently, many of the areas served were left with no library service whatsoever. Some effort was made to retain the existing collections, being made available in county courthouses. However, the delivery service needed for isolated communities was no longer available, leaving some communities without access to books for decades until bookmobiles were introduced to the area in the late 1950s.

(Source)